| ||||

|

Month: March 2006

-

-

St Patrick the Bishop of Armagh and Enlightener of Ireland

Saint Patrick, the Enlightener of Ireland was born around 385, the son of Calpurnius, a Roman decurion (an official responsible for collecting taxes). He lived in the village of Bannavem Taberniae, which may have been located at the mouth of the Severn River in Wales. The district was raided by pirates when Patrick was sixteen, and he was one of those taken captive. He was brought to Ireland and sold as a slave, and was put to work as a herder of swine on a mountain identified with Slemish in Co. Antrim. During his period of slavery, Patrick acquired a proficiency in the Irish language which was very useful to him in his later mission.

He prayed during his solitude on the mountain, and lived this way for six years. He had two visions. The first told him he would return to his home. The second told him his ship was ready. Setting off on foot, Patrick walked two hundred miles to the coast. There he succeeded in boarding a ship, and returned to his parents in Britain.

Some time later, he went to Gaul and studied for the priesthood at Auxerre under St Germanus (July 31). Eventually, he was consecrated as a bishop, and was entrusted with the mission to Ireland, succeeding St Palladius (July 7). St Palladius did not achieve much success in Ireland. After about a year he went to Scotland, where he died in 432.

Patrick had a dream in which an angel came to him bearing many letters. Selecting one inscribed “The Voice of the Irish,” he heard the Irish entreating him to come back to them.

Although St Patrick achieved remarkable results in spreading the Gospel, he was not the first or only missionary in Ireland. He arrived around 432 (though this date is disputed), about a year after St Palladius began his mission to Ireland. There were also other missionaries who were active on the southeast coast, but it was St Patrick who had the greatest influence and success in preaching the Gospel of Christ. Therefore, he is known as “The Enlightener of Ireland.”

His autobiographical Confession tells of the many trials and disappointments he endured. Patrick had once confided to a friend that he was troubled by a certain sin he had committed before he was fifteen years old. The friend assured him of God’s mercy, and even supported Patrick’s nomination as bishop. Later, he turned against him and revealed what Patrick had told him in an attempt to prevent his consecration. Many years later, Patrick still grieved for his dear friend who had publicly shamed him.

St Patrick founded many churches and monasteries across Ireland, but the conversion of the Irish people was no easy task. There was much hostility, and he was assaulted several times. He faced danger, and insults, and he was reproached for being a foreigner and a former slave. There was also a very real possibility that the pagans would try to kill him. Despite many obstacles, he remained faithful to his calling, and he baptized many people into Christ.

The saint’s Epistle to Coroticus is also an authentic work. In it he denounces the attack of Coroticus’ men on one of his congregations. The Breastplate (Lorica) is also attributed to St Patrick. In his writings, we can see St Patrick’s awareness that he had been called by God, as well as his determination and modesty in undertaking his missionary work. He refers to himself as “a sinner,” “the most ignorant and of least account,” and as someone who was “despised by many.” He ascribes his success to God, rather than to his own talents: “I owe it to God’s grace that through me so many people should be born again to Him.”

By the time he established his episcopal See in Armargh in 444, St Patrick had other bishops to assist him, many native priests and deacons, and he encouraged the growth of monasticism.

St Patrick is often depicted holding a shamrock, or with snakes fleeing from him. He used the shamrock to illustrate the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Its three leaves growing out of a single stem helped him to explain the concept of one God in three Persons. Many people now regard the story of St Patrick driving all the snakes out of Ireland as having no historical basis.

St Patrick died on March 17, 461 (some say 492). There are various accounts of his last days, but they are mostly legendary. Muirchu says that no one knows the place where St Patrick is buried. St Columba of Iona (June 9) says that the Holy Spirit revealed to him that Patrick was buried at Saul, the site of his first church. A granite slab was placed at his traditional grave site in Downpatrick in 1899.

Click here to see last year’s post on this day.

-

~How Did Orthodoxy Escape the Culture Wars?~

Ancient Faith, Modern Life

Orthodoxy: Unbruised by the Culture Wars

Why aren’t Orthodox Christians fighting over gay marriage, women priests, and more? Because we accept the wisdom of the past.

“What are the controversial issues in Orthodoxy?” This question, recently posed on a Beliefnet message board, is the dandelion in the lawn of Orthodox inquirers. It’s the question I kept asking, fifteen years ago, when my family was deciding to leave our mainline denomination. If we became Orthodox, what would we be getting into? Was it going to be the same heartbreaking arguments over sexuality, scripture, and more–just over pierogies instead of doughnuts?

Well, there are controversies in Orthodoxy, all right, but they’re not those controversies. You can find people on the internet arguing heatedly about whether churches should follow the old or the new calendar, or whether Orthodox should participate in any kind of ecumenical dialogue. But the fierce internet debates don’t seem to come up much at the parish level (though you’ll find garden-variety power struggles, nominal faith, and other frustrations that plague any church).

Some very big controversies are actually on the mend. For a century there was a split between those Orthodox who left Russia in order to preserve the faith, and those who stayed behind. But on the feast of Pentecost (June 19, 2005), leaders of both bodies signed an agreement that paves the way for reunion. That’s cause for rejoicing.

So, yes, there are controversies–but that’s not what American inquirers mean. What about gay marriage? What about women’s ordination? Is there an abortion-rights movement in Orthodoxy? Are there bishops who teach that the Resurrection was a myth?

Those are the questions causing turmoil in most American denominations. When my husband and I began looking into Orthodoxy, gay issues weren’t yet on the horizon, and we didn’t have any problem with women’s ordination. (I attended seminary myself and sought ordination, until I got a good look at how hard a pastor’s job is.) What concerned us instead was theological upheaval – for example, bishops questioning the Virgin Birth, miracles, and the bodily Resurrection. We wanted to find a place where our children could be secure in the original faith. My husband had a T-shirt that read, “Have a Nicene Day!”

But as I moved toward my chrismation I felt worried. I could see that Orthodoxy was preserving the faith just fine – for now. But it had no visible means of enforcing that faith. The Orthodox hierarchy doesn’t have the kind of power that high-ranking clergy do in other churches. There isn’t even a worldwide governing board to hold all the various Orthodox bodies together. On the ground it looked pretty ad hoc, especially in America, where waves of immigrants have set up parallel administrative bodies.

And there didn’t even seem to be an Orthodox catechism, for goodness’ sake. It seemed like the faith was supposed to be learned almost by osmosis, by living it. How could that work? If a church with an infallible pope and a magisterium could have as much rioting in the pews as the Catholics did, what hope did the Orthodox have? So I figured it was just a matter of time. Trying to maintain the classic faith without a powerful hierarchy didn’t look like doing a high-wire act without the net; it looked like doing it without the wire.

The following fifteen years have been devastating to the peace of most American churches. People who have lived through these battles are battered and worn. And yet – unbelievably enough — Orthodoxy has remained untouched. It’s as if the contemporary American furor is just a tiny blip in history, and not our concern. We still don’t have demands for gay marriage, or nuns agitating for women in the priesthood. We don’t see theological revision or liturgical innovation. The biggest controversy today would be the painful wrangle among Greek Orthodox about their charter – yet, when it comes to theological and moral issues, people on both sides still believe the same things. That’s what being Orthodox means: holding a common faith. All the “big questions” were settled over a millennium ago, and no one is inclined to revise them.

How can we resist the cultural tides this way? I have a theory. I think it’s because you can only change something if you have the authority to change it. You have to be in a position of power, enabled to explain and define the faith anew; or you can battle noisily against those in that position, and make it awkward for them to use their power. In any case, faith is understood as something eternally under construction, responding to the challenges of each new generation.

But in the Orthodox Church, nobody has that kind of power. The church is too decentralized for that. Even those who are our leaders are a different kind of leader. Orthodoxy is less of an institution (like, say, the Episcopal Church) and more of a spiritual path (like Buddhism). It’s a treasury of wisdom about how to grow in union with God–theosis.

And that wisdom works, so people don’t itch to change it. It doesn’t need to be adapted to a new generation, because God is still making the same basic model of human being he has from the beginning. Practitioners of the way don’t find it irksome or boring; they just want to get into it deeper. For us, authority is not located in a person or an organization, but in the faith itself–what other Orthodox before us have believed.

Every question is settled by asking, “What did previous generations believe?” And since previous generations asked the same thing, the snowball just keeps getting larger. Against that weight of accumulated witness, a notion that blew in on the cultural breeze doesn’t stand a chance.

What’s surprising is that there is so little variation from culture to culture. As missionaries carried Christianity to new lands, each new outpost looked back to the “faith once delivered.” So Russian, Greek, Romanian, Antiochian and other Orthodox all share the same beliefs. Even the Oriental Orthodox, the Armenians and Copts and others, who have been separated from us since the fifth century, still look an awful lot like us. They, too, are looking back toward the authoritative early faith.

So someone who wanted to challenge Orthodoxy would not be able to locate a building to hold a protest march in front of. The faith is too diffused. And what if a high-ranking hierarch attempted to enforce innovations? He’d be recognized as a kook and rejected. Anyone who disagrees with the inherited faith has stepped outside the building.

Although we don’t have innovation, we do have nominalism. Lots of Orthodox go to church every Sunday but don’t know much about the faith. Yet they know that there is something that they don’t know much about. They don’t try to redefine “Orthodoxy” to cover whatever they’re doing or not doing. If they’re dissatisfied, if they want something more contemporary, if they want to attend a more “American” church, there are plenty they can choose from.

And meanwhile, of course, lots of people are coming in the other door. The Dallas Morning News reports that, in the Antiochian Archdiocese, 78% of the clergy are converts. This means an infusion of parish leaders who are very well-informed about theological and cultural issues, and very intentional about why they have become Orthodox (sometimes at great personal sacrifice).

So instead of spending the last fifteen years fighting and worrying and being bruised in a hostile denomination, I’ve been able to focus on the face of Jesus Christ. I’ve been able to dig deeper into awareness of my own sinfulness, and take baby steps toward spiritual healing. I’m able to worship in an ancient communion full of awesome beauty, one that is now being blessed with quiet revival. My one regret? That I didn’t do it sooner.

-

~Are we too busy for God? ~

Fr. Steven makes some excellent points.

From the perspective of within/inside, Great Lent is an intense parish activity that absorbs the time and energy of the parish in ways that are wholesome and spiritually fruitful. We are “keeping Lent” together, as a body of believers. We understand the signs and symbols of Great Lent and what is expected of us in terms of our personal effort. We then make an honest attempt to make our homes an extension of the Church (the home is a “little church” according to St. John Chrysostom), by creating some further signs of a “lenten atmosphere” in our homes within our families. (For the moment, the point is not whether we are successful or not – we are speaking of intentions and effort).

However, from the perspective of without/outside, meaning our secularized society or the world at large, Great Lent has no impact whatsoever. It is not being observed (even if the occasional restaurant sign may advertise a lenten meal on Fridays!), and the world will not lose a beat in its hectic rhythm of unending activity because certain Christians are observing a lenten season. Nothing outside of the Church will stop for our sakes, and life continues with its daily round of demands and responsbilities. Outside of public discourse or social/cultural recognition, Great Lent becomes a highly personalized religious endeavor. We can test this with a simple question: Do your next door neighbors know that you are now observing Great Lent? This is even more the case for us as Orthodox Christians because we are such a minority. Schools may close for the western Good Friday, but not for our Great and Holy Friday observed on a different date.

Since life continues essentially unchanged, and we remain as “busy” as ever, we may be tempted to say to ourselves, consciously or unconsciously: ”I am too busy for Lent.” Or: “How can I possibly integrate almsgiving, prayer and fasting into my life when I hardly have a second in which to catch my breath?” Or with a further touch of frustration: “The Church should get more realistic and change its expecations of the faithful in this day and age.” I fully acknowledge the reality that prompts such a series of thoughts. And that reality affects us all – the priest’s family (since he and his family do not live in some sort of mysteriously protected vacuum) and well as the families of all parishoners. My pastoral concern with the thought “I am too busy for Lent,” is the following: it is dangerously close to the thought ”I am too busy for God.” No one would admit to such a thought, of course, but that could be the practical result of excusing ourselves through our busy-ness.

Making the near-equation between “I am too busy for Lent” and “I am too busy for God,” is based upon the fact that Lent is all about God. Whatever image we employ, a School of Repentance, a Journey to Pascha, A Season of Abstinence, etc., the meaning of Great Lent is to bring us closer to God. We drift away from God or take God for granted in our lives. Through repentance, strengthened by the tools of almsgiving, prayer and fasting, we return to God in a spirit of humility and contrition: “Have mercy on me, O God, have mercy on me.” Eliminating Lent from our lives outside of some nominal practices will have the effect of marginalizing God even further by either the endless and essential activities thrust upon us; or the empty distractions willing embraced by us.

If we are indeed “too busy for Lent,” then we will too busy to practice the following based upon constraint of time, exhaustion of mind and body, or preoccupation with other attractions:

praying with consistency and concentration

fasting beyond the nominal

reading the Scriptures

attending the services peculiar to Great Lent

seeing a neighbor in need of assistance

participating in parish Retreats meant to deepen the lenten experience

In today’s world, many of the faithful only know that its Lent by the priest’s lenten-colored vestments worn on Sunday morning! This is not meant reproachfully, but as a pastoral reminder of the many challenges set before us by conditions as they exist today. There would be no worthy reason to remind anyone of this if nothing could be changed. Otherwise, we would only invite discouragement or “guilt.” But I am convinced that some things can be done, and need to be done if we are going to take Lent seriously. I am convinced that we can examine our priorites with care and responsbility and make the kind of “adjustments” needed to maximize our lenten effort by stressing the essential over the non-essential. Perhaps we could offer as a working definition of Great Lent in our current social and cultural climate as the rediscovery of the essential over the non-essential in our lives. Based on the Gospel that would be the love of God and neighbor (and if we are really “too busy,” the “neighbor” could be our family members!) over “mammon” and “treasures on earth.” (cf. MATT. 5:19-20, 24) In the words of Fr. Alexander Schmemann:

However new or different the conditions in which we live today, however real the difficulties

and obstacles erected by our modern world, none of them is an absolute obstacle, none

of them makes Lent “impossible.”

Let us now set out with joy upon the second week of the Fast; and like Elijah the

Tishbite let us fashion for ourselves from day to day, a fiery chariot from the four great

virtues; let us exalt our minds through freedom from the passions; let us arm our flesh

with purity and our hands with acts of compassion; let us make our feet beautiful with

the preaching of the Gospel; and let us put the enemy to flight and gain the victory.

(Sticheron, Vespers of the First Sunday of Great Lent)

-

Tonight was Awesome!!!

Affirmation Of Faith , from the Seventh Ecumenical Council ~ Nicea, Asia Minor in 787 A.D.

As the Prophets beheld,

As the Apostles taught,

As the Church received,

As the Teachers dogmatized,

As the Universe agreed,

As Grace illumined,

As the Truth revealed,

As falsehood passed away,

As Wisdom presented,

As Christ awarded,

Thus we declare,

Thus we assert,

Thus we proclaim Christ our true God

and honor His saints,

In words,

In writings,

In thoughts,

In sacrifices,

In churches,

In holy icons.

On the one hand, worshipping and reverencing Christ as God and Lord.

And on the other hand, honoring and venerating His Saints as true servants of the same Lord.

This is the Faith of the Apostles.

This is the Faith of the Fathers.

This is the Faith of the Orthodox.

This is the Faith which has established the Universe.

AMEN! -

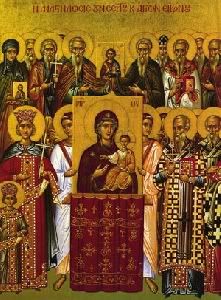

Every year, the first Sunday of the Great Lenten Fast is called “Orthodoxy Sunday.” It is dedicated to the Restoration of Icons on the first Sunday of the Great Lent/Fast in the year 843. It is always celebrated as a “Triumph of Orthodoxy,” a triumph over those who sought to defeat and undermine the Orthodox Faith of the Apostles and the Church Fathers by prohibiting the use and veneration of icons. Thousands of devout Orthodox Christians were martyred for their Faith during the approximately 125 years that the Holy Orthodox Church endured the imposition of iconoclasm.

In the United States, because of the presence of various different ethnic expressions of the one Orthodox Faith, it has become traditional in many cities on Orthodoxy Sunday, especially in large metropolitan areas, for Orthodox Christians of all ethnic traditions and jurisdictions to come together and witness to, and proclaim the unity of the Faith of the apostles, the Faith that has been maintained in the Orthodox Church for 2,000 years.

How can we understand the meaning of this day, this Triumph or Feast of Orthodoxy? How can the victory over iconoclasm be a triumph of Orthodoxy itself? The triumph of icons is a triumph of Orthodoxy: without icons, there is no Orthodox Christianity. Icons affirm the basic principle of the preaching of the Gospels — interpreted in the decisions of the Seven Ecumenical Councils — namely, that God became man in Jesus the Christ, in order to reconcile the world to Himself. It is precisely because God took on a material form in Jesus, that we can make images of Jesus and of His true servants, the saints. These images or icons furthermore affirm that the material world participates in salvation — that is, in the process of the transfiguration and resurrection of humanity and of all the cosmos. The material world is good, because God created it and incarnated in it, and He continues to manifest Himself to us in material form — especially in the Holy Mysteries (Sacraments), in icons, in the Gospels and the cross. We do not worship these things, for worship is given only to God. Neither is it their material substance which we venerate when we kiss them; rather, our veneration is passed on to the prototype. We can express our love for Jesus by kissing His icon or cross, but it is Christ — not paint and wood — whom we venerate by means of His icon or cross. ~ article taken from here.

-

I have been meaning all week to change my blog color to reflect the Lenten season.

Tomorrow Sunday March 12th is the first Sunday of Lent and the Sunday of Orthodoxy.

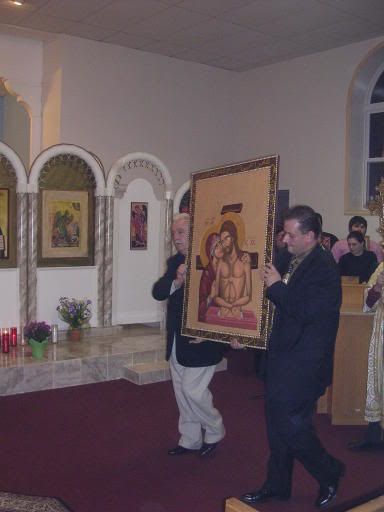

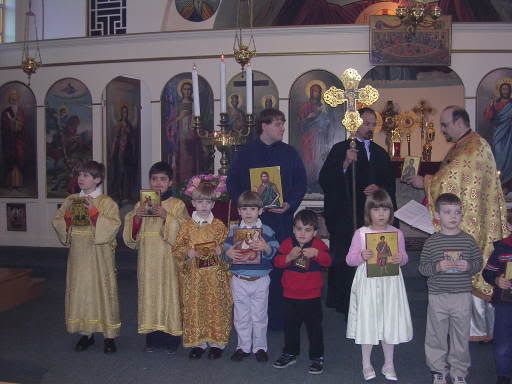

On this feast day there is a procession in remembrance of the victory over the iconoclasts.

In our Greek Orthodox parish and most of those I know the children of the church along with the clergy make a procession around the interior of the Church holding icons. (I hope to take pictures of the children with the icons of their patron saints and post them soon.)

In the evening many cities and towns there is usually a Pan-Orthodox Sunday of Orthodoxy Vespers; sometimes a Pan-Orthodox Liturgy is held in the morning instead.

Tomorrow night the local Antiochian parish nearby will be hosting all the other Orthodox parishes in the area.

I encourage all of you to attend your local Sunday of Orthodoxy Divine Liturgy and vespers. Pan-Orthodox vespers is a wonderful opportunity to pray and fellowship with our other fellow Orthodox Christians.

First Sunday of Lent: The Sunday of Orthodoxy

Lent was in origin the time of final preparation for candidates for baptism at the Easter Vigil, and this is reflected in the readings at the Liturgy, today and on all the Sundays of Lent. But that basic theme came to be subordinated to later themes, which dominated the hymnography of each Sunday. The dominant theme of this Sunday since 843 has been that of the victory of the icons. In that year the iconoclastic controversy, which had raged on and off since 726, was finally laid to rest, and icons and their veneration were restored on the first Sunday in Lent. Ever since, that Sunday been commemorated as the “triumph of Orthodoxy.” Orthodox teaching about icons was defined at the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787, which brought to an end the first phase of the attempt to suppress icons. That teaching was finally re-established in 843, and it is embodied in the texts sung on this Sunday.

From Vespers:

“Inspired by your Spirit, Lord, the prophets foretold your birth as a child incarnate of the Virgin. Nothing can contain or hold you; before the morning star you shone forth eternally from the spiritual womb of the Father. Yet you were to become like us and be seen by those on earth. At the prayers of those your prophets in your mercy reckon us fit to see your light,

“for we praise your resurrection, holy and beyond speech. Infinite, Lord, as divine, in the last times you willed to become incarnate and so finite; for when you took on flesh you made all its properties your own. So we depict the form of your outward appearance and pay it relative respect, and so are moved to love you; and through it we receive the grace of healing, following the divine traditions of the apostles.

“The grace of truth has shone out, the things once foreshadowed now are revealed in perfection. See, the Church is decked with the embodied image of Christ, as with beauty not of this world, fulfilling the tent of witness, holding fast the Orthodox faith. For if we cling to the icon of him whom we worship, we shall not go astray. May those who do not so believe be covered with shame. For the image of him who became human is our glory: we venerate it, but do not worship it as God. Kissing it, we who believe cry out: O God, save your people, and bless your heritage.

“We have moved forward from unbelief to true faith, and have been enlightened by the light of knowledge. Let us then clap our hands like the psalmist, and offer praise and thanksgiving to God. And let us honor and venerate the holy icons of Christ, of his most pure Mother, and of all the saints, depicted on walls, panels and sacred vessels, setting aside the unbelievers’ ungodly teaching. For the veneration given to the icon passes over, as Basil says, to its prototype. At the intercession of your spotless Mother, O Christ, and of all the saints, we pray you to grant us your great mercy. We venerate your icon, good Lord, asking forgiveness of our sins, O Christ our God. For you freely willed in the flesh to ascend the cross, to rescue from slavery to the enemy those whom you had formed. So we cry to you with thanksgiving: You have filled all things with joy, our Savior, by coming to save the world.

The name of this Sunday reflects the great significance which icons possess for the Orthodox Church. They are not optional devotional extras, but an integral part of Orthodox faith and devotion. They are held to be a necessary consequence of Christian faith in the incarnation of the Word of God, the Second Person of the Trinity, in Jesus Christ. They have a sacramental character, making present to the believer the person or event depicted on them. So the interior of Orthodox churches is often covered with icons painted on walls and domed roofs, and there is always an icon screen, or iconostasis, separating the sanctuary from the nave, often with several rows of icons. No Orthodox home is complete without an icon corner, where the family prays.

Icons are venerated by burning lamps and candles in front of them, by the use of incense and by kissing. But there is a clear doctrinal distinction between the veneration paid to icons and the worship due to God. The former is not only relative, it is in fact paid to the person represented by the icon. This distinction safeguards the veneration of icons from any charge of idolatry.

Although the theme of the victory of the icons is a secondary one on this Sunday, by its emphasis on the incarnation it points us to the basic Christian truth that the one whose death and resurrection we celebrate at Easter was none other than the Word of God who became human in Jesus Christ.

-

Today Saturday March 11 is the last of the three Saturday of the Souls Divine Liturgies and the first Saturday of Great Lent. I am always amazed at how much I learn by doing this blog; I know the posts are long but the history is so interesting.

-

Tonight is the first of five Akathist hymns chanted of the first 5 Fridays during Lent. If your church offers the Akathist I would encourage you to attend; the Akathist is a very beautiful service. Here is the full service.

The Akathist (Salutations) to the Mother of God

The Akathist Hymn and Small Compline are two services which are sung on the first five Fridays during Great Lent.